Welcome to the Western Collaborative Conservation Network’s profile series “Collaboratives Behind-the-Scenes.” This series features Q&As with different conservation organizations to provide a view into what it takes to run a collaborative organization from challenges faced in building partnerships to tips for budding organizations. Whether you’re already running a collaborative and are looking to increase your efficiency or are thinking of starting a collaborative but want to know more about what you’re getting into, we hope you find this series insightful.

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies sums up its vision with one simple statement: “We believe the world needs birds.” Bird Conservancy, a 501c(3) nonprofit, works to conserve birds and their habitats through science, education, and land stewardship. To meet this mission, Bird Conservancy works across the West, from Mexico to Canada, conducting research and monitoring bird populations, hosting bird camps for kids and bird banding events, conducting habitat enhancement projects and providing resources for landowners, and so much more.

We had the pleasure of speaking with the conservancy’s Executive Director, Tammy VerCauteren. Tammy shared her experiences working with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies for the past two decades and the strategies they use to increase public awareness and expand opportunities for collaboration. At the end of our discussion, Tammy provided us with a wonderful summary of all she has learned as a conservation scientist:

“Having good ideas that are relevant to stakeholders, being open to hearing different voices and perspectives, being true and intentional in your engagement approaches – this all contributes to creating an authentic process that brings voices and values forward, and being open to change and some uncomfortable conversations. If you’re true to the people and the purpose, you’ll be able to work through those. People will see and value that, and trust and relationships will deepen.”

Read on to learn more about Tammy’s work experiences and wisdom!

Note: This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How did you get involved in Bird Conservancy of the Rockies?

I was hired 23 years ago. I was hired because I had worked with landowners in Nebraska to get access to their grasslands for my sandhill crane research. What was then Colorado Bird Conservancy became Rocky Mountain Bird Conservancy, and is now Bird Conservancy of the Rockies– they had started a ‘Prairie Partners’ program and the staff had come together and said, “Look, there’s a set of birds that are declining, we don’t know much about them, and they are on private lands. What could we do to help understand these birds, understand the people, and figure out collaborative solutions for conservation?” So, I started as the Prairie Partners Coordinator for Wyoming/Colorado and the GIS specialist.

And pretty much immediately, I started to sleep in my car and talk to ranchers about grassland birds and did bird surveys. I was there in the communities talking to people and there was a neighbor-to-neighbor communication which snowballed. As I built trust and relationships, they opened doors to other people. I was referred to in the community as either “The Bird Lady” or “The Owl Lady,” which was great!

I worked for a nonprofit that had no regulatory authority. I was just out there trying to get a handle on where these birds were, particularly burrowing owls. I had candid conversations with landowners who thought that, because I knew the birds were on their property, they would get in trouble. And I would assure them, “No, actually your information is power. The more we find the better. If we can’t count them, we make our best estimate”. I think that definitely opened some eyes. I was trying to understand their culture and challenges.

Not too long after I got started, I thought, “Well, gosh. If I want them to have conversations about birds, maybe I should be having conversations about ranching and learning about what they’re doing.” So I was fixing fences, helping with calving, going to brandings, and just learning about that way of life. I would weave birds into the conversations and make connections between grasslands, grazing, and birds. The common ground was land–they cared about and were passionate about the land.

When it comes to working in these communities, you are a face, you’re a name, you invest, you meet them where they are, you listen to them, and you start conversations. It’s about being willing to meet people where they are and be honest and transparent.

How does the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies as an organization use a collaborative approach in its work?

Collaboration plays into pretty much everything we do and at all levels. Our Private Lands Wildlife Biologists on the ground in Colorado are already in a shared position with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and likely also the Colorado Parks & Wildlife. We have replicated this model across other states as well. They start with a multi-partner, multi-funder community. We try to have foundations and individual donors that help make the position whole, offer more resilience and flexibility and help ensure the biologist can deliver on multiple priorities that bring us all together. The Natural Resources Conservation Service has their priorities, CO Parks and Wildlife has theirs. Bird Conservancy has our values and mission, our goals and strategies. So, this person helps focus on where all of those priorities come together and meets landowners where they are.

Our Land Stewardship approach is about caring for the land, the birds that call it home, and the sustainability of bird habitats.It all goes back to land and its health and vitality. How is the land doing? How’s the soil? How’s the water? How’s the productivity? Where are opportunities for improvement? What are the landowner’s priorities, and what do they see as threats and resource concerns? What do we observe from our perspective, using science as a guide? ? How can we work together on a conservation plan and improve things together? We build from that ground level, and make it more transferable so it reaches the state and then the region.

From an education perspective, our programs start with toddlers and go all the way up through high school, college students, adults, and retired folks. We use different tools and create experiences and opportunities including bird banding, exploring in nature, connecting with the prairies, and firsthand learning about conservation of water and other natural resources. At the end of the day, your goal is to help people grow in nature, whether they’re three years old or still bringing the positive experience of nature to someone in a retirement facility. To do that takes partnership because we can’t do it all. Obviously we have a bird focus but we also have a habitat focus and a place focus and we are trying to have more sustainable communities recognize that what you plant and grow in your community park or backyard makes a difference. Whenever possible, we partner with allies to leverage resources.

We’ve also done interesting collaborations with Tier One Schools, which are schools with economic challenges. We want to make sure that we’re bringing science, technology, engineering, arts, and math to these children and their families. Alongside the Colorado Ballet, the Butterfly Pavilion, and the Botanical Gardens, we are working from kindergarten through third grade, so kids are getting meaningful outdoor experiences and they’re learning about movement, art, creativity, science, and nature. We also have community days with the families to support that love of nature in the parents and make it possible to make those beneficial connections.

With science, one of our biggest programs is bird monitoring. We’re trying to get an accurate sense of what’s happening to their populations and how those trends relate to what is changing on the landscape. If people are actively managing for conservation goals, is it effective and how is it affecting the birds? Are there management strategies that are better for birds while benefiting other wildlife too? The Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR) program has over 20 partners at the table and is the second largest bird monitoring program in North America, spanning 14 U.S. states. The idea is to have a collaborative and integrative approach for monitoring across our partnerships to create an accessible baseline of data on private and public lands to compare results.

How do you approach relationship-building and collaboration on a regional scale?

We approach this multiple ways. We are part of Joint Venture Boards established by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. They are meant to be regional and have been defined by Bird Conservation Region Boundaries. There is a coordinator in place that can be with Fish & Wildlife Service or a non-government person, depending upon the arrangement. You might have Fish & Wildlife, non-government organizations, state wildlife agencies, other federal partners, and in some cases private landowners and other communities or industries, all at the table. The idea in this model is that together you can do it better. Birds migrate, so we have to work across boundaries in the places where birds pass through, where they spend their winters and breeding seasons. At the end of the day, you need all of these people and places coordinating and working together.

I am also a part of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, which is a national organization designed to bring collaboration, communication, and guidance on how to deliver bird conservation more effectively. It also has partnerships with Canada and Mexico. Again, here we are at the table with additional cohorts, federal, state, and private stakeholders, and NGOs.

The other most recent effort is the Grasslands Roadmap. The reality is when you look at the grasslands landscape in our region, we are losing acres every day, water is running out in communities, wildlife is declining – whether its birds, pollinators, pronghorn. They’re all headed in a negative trajectory. There are a lot of great people doing work but we are not creating a movement for grasslands. And, we’re not coordinated and aligned on what are the greatest priorities that we need to be addressing.

So, we looked at who lives and works in these landscapes. The stakeholders represent four nations– Canada, Mexico, U.S., and Sovereign Tribal Nations– and seven sectors– the NGOs, the Federal and state governments, the academics, foundations, industry, and landowners. We all live here, our footprint matters. What would it look like if we were all part of the conversation? And we were all bringing all of our distinct values and knowledge to the table to chart a collaborative course forward and change the trajectory of our grasslands. It’s over 600 million acres; less than 100 million are still intact grasslands. Another 100 million are still grasslands, but they are at risk of conversion or being invaded by trees and shrubs and invasive grasses. The rest are gone. They are either no longer grassland communities any more because of desertification and shrub encroachment, or have been plowed for agriculture. How can you address 600 million acres strategically and effectively, and get the leverage, awareness, and resources to do it better?

So, we came together as a community and talked about partnerships, engagement, policy, and funding. What are the science, research, and knowledge gaps holding us back? Do we have equitable access to programs? No. What does that look like and how do we address that? Grasslands are a common denominator in our cultural values. In this forum we elevated Indigenous voices to the same level as everybody else with the belief that Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge is critical to the future of our grasslands. It’s not bison versus cattle. It’s grazers and animals out there on the landscape keeping the grasslands healthy. There are so many things pulling at each other. But if we can really get a movement for grasslands and better coordination and funding, we can put the issue on the radar of our countries and partners.

How do you maintain interest in your organization over time from the public and other groups?

These are questions that we are always trying to figure out. It’s about staying in tune to what people care about, what’s happening in our environment and landscapes, and helping show how conservation matters and is relevant to communities and peoples values.

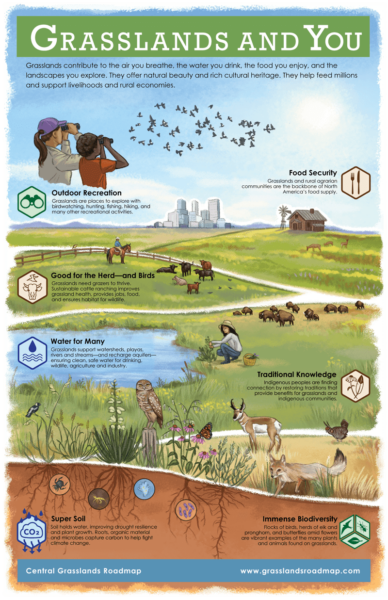

For example, we created a campaign through our communications team which is about Grasslands and You. The air you breathe in Denver, the water you drink, is touched by, influenced, and conserved by grasslands. People don’t know that. It’s that awareness and engagement and relevance.

Birds are in decline– why does that matter to me? Well, what do birds do on that landscape? They pollinate plants, disperse seeds, and help with pest control. Do we appreciate all those things? Plus, just the joy, the color, and song they bring to our world. Once you’re aware, it’s hard to ignore. And once they’re aware, can you then touch their heart and motivate them to want to contribute in ways from their own backyard, to where they donate, to how they vote.

There’s so much information out there–soundbites, social media posts, good visuals, captivating messaging that can be accessible in different ways and for people with different needs (i.e. colorblindness, visual impairments, etc.). We have to be mindful of these things to be effective and ensure access for everyone.

What are some specific tips you have for building and strengthening partnerships with a diversity of groups?

One thing we started out with was a planning team. [For the grasslands campaign,] we got the four nations and the seven sectors and representatives planning the meeting and what it would look like. I think because of COVID it was more effective because we had to slow it down. We had a virtual conference in 2020, we elevated the voices, we sent out a survey to get people’s perspectives on what they see for the future of grasslands and their values. And then we had that virtual summit and people were saying, “We need things that elevate grasslands in the policy realm so we can get more funding” and, “We need more information networking and sharing across communities.” Now we have landowners in Mexico talking to landowners in Montana about how they are doing grazing management and they are learning from each other!

From that effort, people said, “This is great. We need time together. We need to come together, and we need more local input.” So in 2021, we had 10 different Working Groups developing different elements. One element was a collaborative map to capture the landscape and the people. Maps either divide you or bring you together, so care was taken to address concerns from all stakeholders. One of the Working Groups focused on Foundations and discussed community priorities for investing in things that will matter to their future. Federal partners like Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the U.S. Forest Service, joined the conversation and explored how their policies and regulations were similar so they could streamline processes and leverage partnerships. We had an Indigenous Working Group that talked about how to get their culture, values, and challenges noticed and valued by others and how to elevate their profile. All of these different working groups continue today, helping to raise voices from the ground up and they helped set the stage for our in-person meeting in May.

The Roadmap Planning Committee worked with a professional facilitation team to ensure the organizations coming ‘to the table’ bring knowledge and skills but also check their ego and logo at the door. Our professional facilitator helped focus on the issues and what brought us together and made sure it was a collaborative process. Then, for the meeting, there was a facilitation team that he had set up based on what we were talking about from economics to land to Indigenous values, so that people were hearing each other, we were building relationships and trust, and we were also prioritizing what we needed to do. I’ve been really impressed by that facilitative model. You always have people in the room that intentionally or unintentionally tend to dominate the conversation. And the facilitators opened the door so that every voice was heard and captured. I think that was another key success point in this effort.

“When you come to the table you needed to bring your knowledge and skills but you have to check your ego and logo at the door.”

-Tammy VerCauteren

What have you found doesn’t work to get stakeholders involved?

Including people as an after-thought instead of inviting them into the conversation early. Often with new initiatives we are results-oriented and driven to get things going as soon as possible, but conservation happens at the speed of trust, relationships, and relevancy. Make sure that what you’re doing is a true need, partners have buy-in and can help inform it, and that you’re open to their suggestions, ideas and needs. We’re doing a better job in the world of conservation at inviting people to the table, but we might need to change the table, so to speak. We have to be open to different values, different cultures, and different ways of solving problems so that we build things together. You’ll get more buy-in if people truly have skin in the game– they contributed to it, their values are in, they helped inform it, and they feel part of it.

Find out more about Bird Conservancy of the Rockies via this video and at their website.