Welcome to the Western Collaborative Conservation Network’s profile series “Collaboratives Behind-the-Scenes.” This series features Q&As with different conservation organizations to provide a view into what it takes to run a collaborative organization from challenges faced in building partnerships to tips for budding organizations. Whether you’re already running a collaborative and are looking to increase your efficiency or are thinking of starting a collaborative but want to know more about what you’re getting into, we hope you find this series insightful.

The Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable led the development of the Yampa Integrated Water Management Plan (IWMP) focused on the Upper, Middle, and Lower stems of the Yampa and Elk River. The IWMP, completed in September 2022, was a collaborative project which combined “community input with science and engineering assessments to identify actions to protect existing and future water uses and support healthy river ecosystems in the face of growing populations, changing land uses, and climate uncertainty.”

We had the pleasure of speaking with Nicole Seltzer, Colorado Basin Program Director at River Network and Project Manager of the Yampa IWMP Advisory Committee. Since 2018, Nicole and 26 other committee members worked diligently with landowners and other stakeholders to develop a river management plan to achieve a long-term sustainable balance between water use and river health. The team is now moving into implementation of those recommendations. You can find the final report of their plan and recommendations here.

Note: This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How did your career in watershed conservation with River Network lead you to the work that the Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable is doing?

I have been working in various capacities related to stakeholder engagement, watershed planning and permitting, and community education on water and rivers in Colorado for twenty years. I’ve had a few different roles in that space but they all connect people and rivers and water management. Six years ago, I started working at River Network which was about the same time I moved from Denver up to Northwest Colorado, near Steamboat Springs. There was a confluence of things that came together at that time– Colorado had just adopted its first water plan and created funding programs and desired outcomes, and I was looking for a change in my life. So, we created a new program at River Network which focused on supporting implementation of the watershed health goals in Colorado’s Water Plan. Through the program, I have had the honor of helping over 20 communities in Colorado develop river management plans for their local rivers and create a “roadmap” for how they, as a community, want to get from where they are today to where they would like to be, as it relates to sustainable water use, river conditions, and river resiliency.

The Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable is one of nine in Colorado. In the early 2000’s, the State of Colorado created a formal network of local partners in each of the state’s major river basins to better understand river conditions on the ground, water supply needs, and water use issues. To do that, the state developed nine Basin Roundtables to work as a sounding board and liaison for state agencies. The state passes funding to the Roundtables each year which they can use to do their own education and outreach within their communities and provide grants for water-related priorities. The Roundtables are also charged with developing their own set of local goals and priorities. The Yampa-White-Green Basin covers the entirety of northwestern Colorado.

How is the Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable structured?

Each of the nine Roundtables are structured differently, based on their charters; but one of the requirements for all the Roundtables is to create a Basin Implementation Plan. The plan lays out a series of goals and objectives agreed upon by their diverse membership and serves as their guiding document for what to accomplish. In northwest Colorado, there was a feeling that progress on our goals and objectives wasn’t moving fast enough. The power of the Roundtable lies in regranting the state’s funding and so there was a lot of money in our bank account but it wasn’t being granted because we weren’t receiving applications.

As a result of this desire to kickstart momentum, the Roundtable spent a year doing stakeholder outreach to understand the best ways to move forward. In 2018, the Basin Roundtable decided to undertake an Integrated Water Management Plan, and created an Advisory Committee– which is made up of a group of individuals from various organizations, including me from River Network. We developed a scope of work and submitted a grant to the state which supplied us with the direction and money to implement a four-year planning process with the objective of making faster progress on the Roundtable’s goals.

Which goals within the past year have you reached to contribute to that mission?

The Integrated Water Management Plan involved a stakeholder outreach component, technical river and water use assessments, and a decision-making process to understand what all of the information we collected meant for us, and what projects and strategies we could recommend. We finished the IWMP Final Report in September of 2022, only a few months ago! The report includes a series of recommendations on where we think the basin needs to go in terms of sustainable water management, water use, and river ecology.

Now, the focus shifts to implementation. The recommendations are almost all collaborative and require responsibilities to be shared across a number of organizations. There is a 40-page document behind the recommendations which identifies who, where the money is coming from, and how to accomplish each goal– it’s a pretty distinct and clear roadmap.

While implementation is a shared responsibility, there’s a core group of organizations within the basin that are carrying the bulk of it. We are developing a more formal conservation collaborative amongst these organizations in order to support implementation. The goals of the collaborative include developing shared metrics, shared funding opportunities, and meeting on a regular basis to hold one another accountable, support each other, and leverage all the different skill sets and missions of each organization.

How do you get stakeholders involved in your work? What works and what doesn’t?

Northwest Colorado is a rural part of the state. A lot of the land in the river corridor is privately owned and used for agriculture. We knew that private landowners were key to implementing any changes in land and water management to make the system more resilient and sustainable. And, we knew that any solutions that we generated needed to be in the landowners’ best interest.

Knowing that our end goal was to come out with ideas that were going to have buy-in, we spent over a year doing structured interviews with landowners up and down the river. We hired two researchers to conduct interviews and we hired an engineering company to do irrigation infrastructure assessments, specifically on the diversion infrastructure in the river.

The engineers talked with landowners about what they found: the weak points and opportunities for improvement. We did this for two reasons. One, we wanted to know more about the infrastructure in the river and the issues it might be causing, and two, we wanted to provide something of value to the landowner. This way, each landowner would receive concrete advice from an expert on how they could improve their water management.

I think it went really well. We used a lot of resources on engineering assessments and all of the stakeholder interviews but it gave us a clear picture of what was happening on the ground and it gave the stakeholders something of value early on in the process. Therefore, when we needed to call them eight months later and ask for their permission to collect field data on their land, many of them said “Yes, no problem.”

To sum all that up into some principles, it’s important to understand what is going to motivate your stakeholders to participate in the process and provide something of value so that they are willing to have conversations in the future. But, at the same time, you can’t ask too much of them. These are busy people and this is not their highest priority. It might be yours, but it’s not theirs! We tried to put ourselves where the stakeholders were gathering rather than asking them to come to us, but it was still a challenge to foster consistent engagement over four years.

What advice would you give other collaboratives who are just starting out?

Well, there are a few things that we did that I would recommend others do and a few things we did that I recommend not to do! Firstly, before we applied for any money to do the work, we spent almost a year digging into what the committee and stakeholders thought needed to happen. Do we want to take the next four years to work on a planning process for the entire basin? Is that a smart idea?

We spent a lot of time building support for the idea of doing a planning process and then used that support to develop a very clear scope of work including what we were going to do, what the budget would be, and the expected outcomes. It was a time-limited project, which was helpful because it wasn’t a working group with open-ended time commitments. For our committee the scope of work, activities, individual roles, operating rules, and financial processes were clear and transparent from the start. That formal organization, codified in a charter, was really important.

Secondly, the Roundtable is not a legally-incorporated entity and doesn’t have staff, so they couldn’t be the fiscal agent for the work our Advisory Committee wanted to do. So, we had to be structured in a unique way. We had to bring on a fiscal agent and pay for their services. I was the project manager through River Network and we also had facilitation and technical consultants. Additionally, two local NGOs hired new staff to do stakeholder engagement and interviews. It really was a cooperative effort.

Because the river cuts through so many political and water management boundaries, there wasn’t one specific organization who felt this work was their mission. Rather, there were several organizations who thought the work was part of their mission. It was a very distributed decision-making process because we had so many different entities acting in different ways because there was no single organization at the top. If you can get away with not having that kind of structure, that would be my recommendation; it was complicated. My advice is to figure out the simplest way that you can get yourself organized but if it needs to be complicated, it’s doable; we did it! You just have to have somebody in the middle of it that is capable of herding a lot of cats.

Lastly, we were very lucky that a large foundation took an interest early in the process and wanted to support the staff time of the organizations doing the work. Therefore, none of us had to rely on the project grant budget for funding, and all of the time put in by NGO partners was an in-kind contribution. The foundation developed grant agreements with five organizations and created shared commitments including clear roles and responsibilities. That was a blessing, because I don’t know if each individual NGO would have stayed engaged for four years if they didn’t have a grant agreement covering their staff’s participation.

Were there any other challenges that the Roundtable’s Advisory Committee experienced that you could warn other young collaboratives about?

One thing that we stumbled over that we could have avoided was the science related to the river’s ecology. We did research on water use: who was using the water and existing water use gaps. That was pretty straight-forward. But when we started talking about the fishery conditions, riparian corridor and habitat conditions, the geomorphology of the river corridor, and channel movement dynamics, about half of the people on the Advisory Committee were new to these topics. So when we were trying to make decisions, some members were still trying to build their knowledge.

We could have done more up-front education on many of the ecology principles which we had hired consultants to assess. So what happened was that when the consultants presented their information, a sizable group within the Advisory Committee pushed back and said, “I don’t understand this and therefore I’m hesitant to believe it” or “This runs counter to what my family has experienced as landowners for the past four generations.” Coming in with the assumption that the science was easy to understand and everyone knows things like river dynamics– that was a stumbling block that could have been avoided.

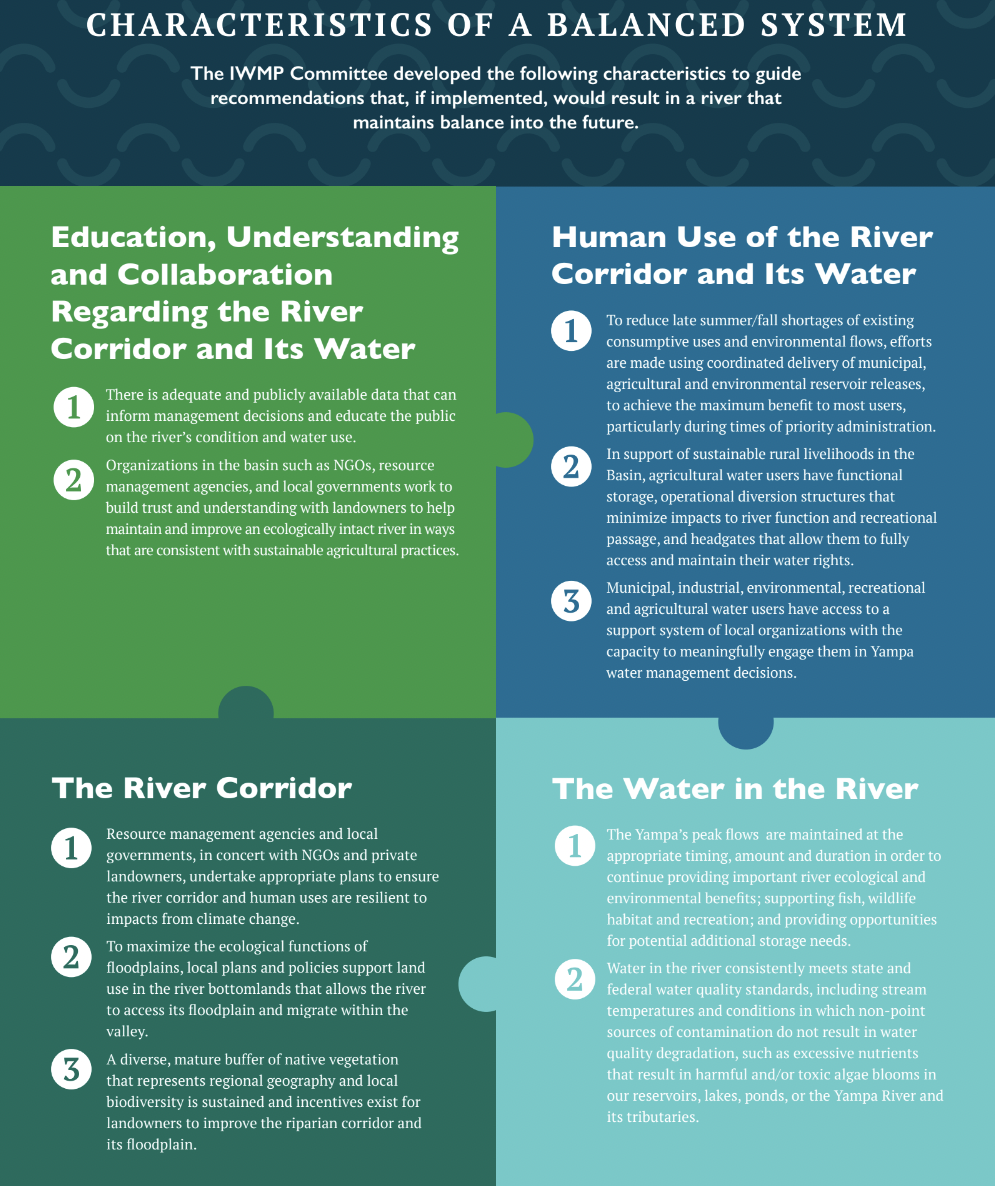

However, I am proud of the unique way in which we resolved that conflict. Our facilitation consultant decided that we needed to take a pause and set the science aside. So we did that for several months. Instead of going down the rabbit hole of geomorphic conditions, we worked on developing a consensus-based definition of what a balanced river system looks like and we got really clear about the defining characteristics of a “balanced river system” between its human uses, demands, and ecology.

The definition is a blending of priorities of all the people who rely on the river for different reasons and have really different goals for the river system. We built this consensus definition to try to bridge those priorities and give us guidance going forward. Working with such a large landscape, (350 miles of river that cuts through many different ecosystem types), what we came away with were high-level principles and recommendations at a landscape-scale. Now the next step for this group is to dive into the specific locations for restoration and prioritization. One plan leads to the next!

What services does River Network provide to conservation groups and what kinds of conservation groups do you provide these services to?

River Network, as an organization, supports river management planning. We have assisted 20 different communities in undertaking river management plans in Colorado up to this point, and the Yampa River is just one of those.

The kinds of services that we provide to coalitions include technical assistance to develop scopes of work and grant applications to fund the planning process. We have a peer learning network of people doing this work in Colorado to support one another as they are going through these processes. And, we are tracking and sharing the methods and outcomes that coalitions are using so that they can learn from each other. We recently built a Colorado Stream Management Planning Resource Library where we keep all of the case studies, examples, and best practices for river management planning. It’s a great place for people to dig into how to do this.

Sometimes, like in the Yampa, we will lead a project if it makes sense. If there’s an overarching reason for why we are the right people and no one else available, and it’s an important landscape, then we will come in and lead. But most of the time, we are supporting local groups that want to do this work.

River Network staff in the Colorado River Basin have developed expertise in integrated, multi-stakeholder planning processes on a large scale and are eager to spread this model. While the subject matter may differ across states, regions, and water challenges, the process and challenges inherent to river planning are often the same. We can’t wait to see how this model is replicated across the nation in the years and decades to come.

Click the following links to find more information about the Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable, the Advisory Committee’s Final Report, and the IWMP’s Interactive Stakeholder Outreach Maps/Graphics.